If we want to unite movements and build a new vision for our society—and the economy that enables it—we have to understand that, according to our guest Dr. Andre Perry from the Brookings Institution, current events are reflecting the very soul of our country. We must have the courage to look into the mirror to see the long and unquestionable history of inequality and racism built into our system’s very architecture.

Glossing over these realities will not get us to something better. We cannot skip over the step of reckoning with our past—and the ways in which this past still haunts us today. This process of reflection is, in fact, the necessary precursor to a brighter future.

While we long for some solid ground—some certainty—if we can muster the courage to open our eyes wide and look into that mirror, we will see not only an ugly past and present of racist policies, but also the beautiful potential for a functioning Democracy, an accessible American Dream, and a more perfect union. What we will also see is hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of civic siblings, with their eyes wide open, embodying the collective courage to dream of and work towards enduring equity.

This is the family we all need to lean into right now. Liberty and justice for all—this is the vision we need to be marching towards.

And thanks to Randy Strickland from Cornerstone Capital, you’ll leave this episode with tangible steps you can take today—right now—to start walking this path.

Learn more by subscribing to our Courage Collective e-letter at www.decadeofcourage.com.

Transcript:

Gulley: A quick note before we dive into this episode, amid the uncertainty that so many of us are feeling right now, I can imagine that it might feel intimidating to step into this space where we’ll peel back the layers to see just how broken our system is, and has been specifically for black families throughout our country’s history. But the truth is there is nothing about this election that makes this work any more or less needed. And for some of us, our privilege might fool us into believing that approaching this work right now is a risk, another opportunity to feel disappointed and let down. But I hope instead that by listening to this episode what you’ll find is a vision worth working towards and a community with whom to share the burden of this work. We hope you’ll have the courage to take a deep breath, and come be with us.

Perry: When I say that there’s nothing wrong with black people that ending racism can’t solve, for me, it means stop blaming people.

So this idea in the American Dream would be real if everyone was supported by policy. If there was a level playing field when it comes to investment and care, and there’s just not. Let’s get to the work of creating policy that can uplift everyone.

Gulley: It’s your host Dana Gulley, and with the help of Dr. Perry, who we just heard from, and Randy Strickland, who we’ll hear from a bit later, we’re gonna get real about the American Dream. To do so, we have to understand the wealth inequality that is driven by our economy, and the ways in which Black communities have been impacted most by this inequality from the outset.

Here, I’m intentionally defining wealth narrowly to mean money and financial assets.

As we learned in our first episode, thanks to neoliberal theory, our economy is designed to accumulate wealth at the top, in the hands of the few, creating a massive gap. According to the Pew Research Center, the gap between the wealth of America’s richest and poorest people more than doubled between 1989 and 2016, a period of just 27 years. Within my lifetime.

But when you look at this gap by race, it’s magnified, by a lot. As of 2016, the typical White family has $171,000 of assets, whereas the assets of a typical Black family amount to just $17,000, or a tenth of that.

But if we focus only on closing this gap, we risk attaching ourselves to the White supremacist mindset that built this status quo system, a system that has enabled the devaluation of Black lives and Black property through racist policies and proposed solutions rooted in shaming.

Instead, as a first step, we need to right the wrongs of these policies. Then we need to create new ones.

We’re more than here for it.

3:00

Gulley.: Welcome back to Decade of Courage, a podcast to inspire and unite thought leaders, business leaders and activists, to transform business and our economy. Again, I’m your host Dana Gulley. And in this episode, we’re focused on understanding the racist policies that have disproportionately and systematically kept Black families from accessing wealth-building opportunities in our current economy. As we learned in our first episode, neoliberal theory taken to the extreme has broken our system for everyone but the richest few over the last fifty years.

Had neoliberal economics not given corporations permission to greedily suck more and more value out of their employees, concentrating those increased profits in the hands of executives and shareholders, there’s evidence to say that the median income in this country would be almost double the $50,000 that is today. Instead, two and a half trillion extra dollars are flowing into the hands of the wealthiest each year. This much, I’ve come to understand.

But the median income for a Black person today is just 61% of that of a White person, and on average, wealth is just 10%. So, I want to understand: why has our system been broken for Black people, always?

To find the answers, we’ll need to go into the history of anti-Blackness that has built into our economy from the very beginning.

Then, we explore what it would look like to turn this on its head, instead centering Blackness as a way to both achieve equity and lift all boats in the process.

If this sounds like a radical idea, it’s important to note that, according to Randy Strickland, Director of Racial Equity Investing for Cornerstone Capital, racial equity is a prerequisite to the very viability of an economic system.

Strickland: There’s no society in the history of humankind that has survived that sort of disparity in terms of wealth, uh, of concentration in the hands of just a few.

4:50

Gulley: While inequality presents a systemic risk for society, the good news is that investing in racial equity by targeting the failings of policies, not people, can lead us to a place of shared abundance for all.

Dismantling White supremacy is largely the work of White people. But centering Blackness to envision something better in the first place? We’re gonna need to unite movements for that.

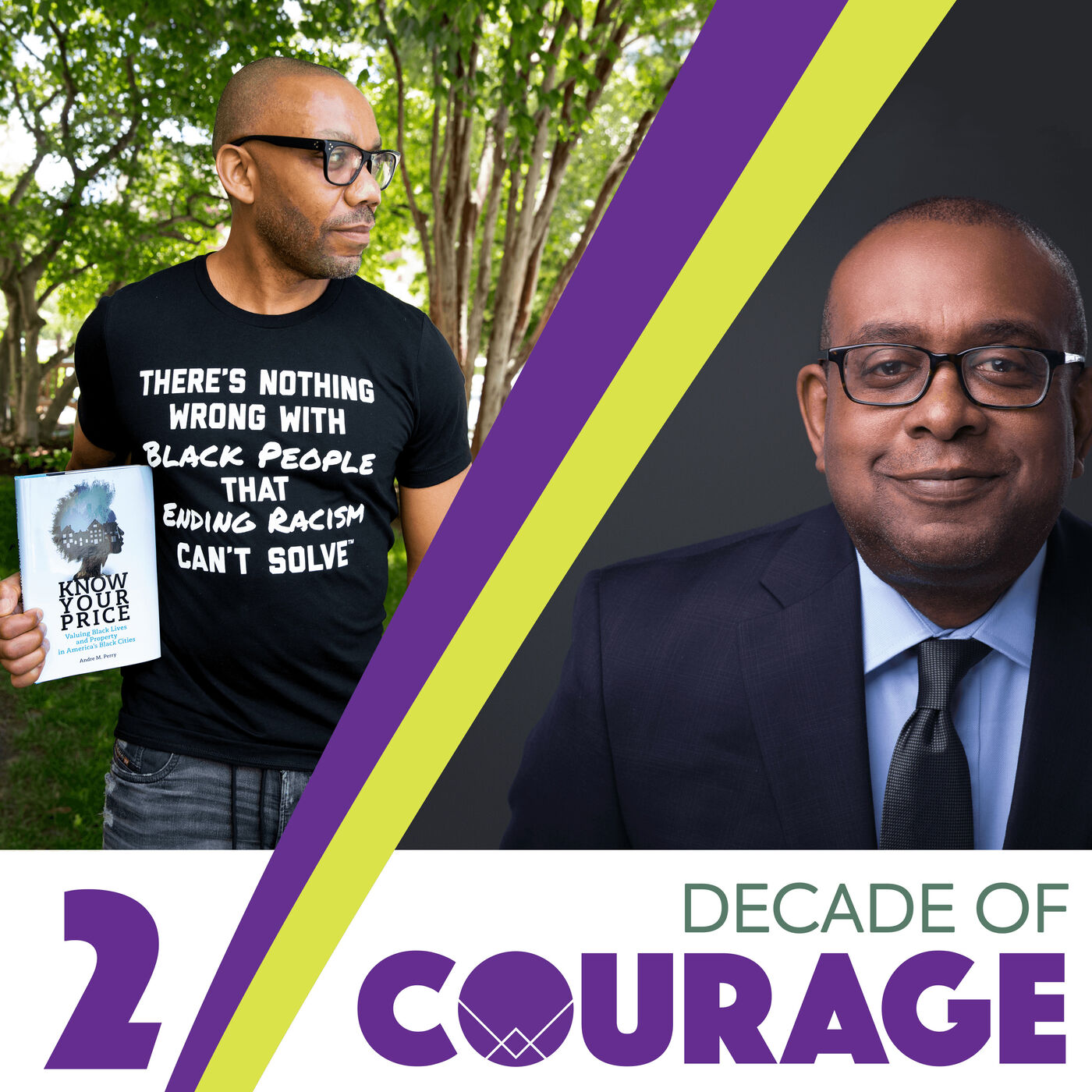

To ground us with a common vision, we asked Dr. Perry, Educator and Research Fellow at the Brookings Institution who we heard from at the top, to share his North Star.

Perry: The person I call mom, um, she is certainly my mother, but I was informally adopted. She took in kids from all walks of life, Black kids, White kids, multiracial kids. And we were family, whether we were related or not.

I see a world in which we are civic brothers and sisters, regardless of your race or your class, your gender, your sexuality. And we operate under the same mother country. That’s what I strive for.

Gulley: Perry gets right to the heart of so much that’s broken right now. And it occurs to me that believing, collectively, in the potential of our mother country – this might just be the necessary foundation for democracy to function in the first place.

But to achieve this vision of the world, we need to be able to accurately reflect, and reflect out loud, on the ways in which Black people have been used as economic resources, rather than engaged as partners or equal beneficiaries of our system.

Perry: Historians and journalists have really elevated the role of slavery in a democracy.

And people really don’t comprehend. I talk about assets all the time, but Black people were assets that were traded, mortgaged, sold, all those different things. So we were valued in a very different way. And, no one saw the potential in us as people, as human beings, and still that haunts us today.

Gulley.: If we want to understand the structural reasons for the racial wealth gap, we have to start with slavery. I feel like in school, I was taught about slavery as a period of time. Approximately 250 years where Black people were brutalized by White people. And then, quite quickly, this period of time was wrapped up as a thing of the past, without any tie-in to the modern day. And on top of all the reasons why this abbreviated history is so obviously wrong, it’s wrong for a reason that I am only just beginning to understand with Dr. Perry’s help.

Perry: Policy facilitates growth.

Gulley. So, if we internalize this notion, we can begin to build another important narrative about the era of slavery. It was the beginning of wealth building for White families in America.

Slavery was the beginning of wealth building for White families in America. Did you ever learn about it this way? If not, you might realize this is a pattern. We have a way of acting like economic success or failure hinges on personal characteristics without really shining the light on the policies that enable or deny wealth creation.

So, let’s quickly look at slavery through the lens of policies: our government stole the land. They sold it to White people for cheap. They enabled free labor because slavery was legal. And White landowners could grow their businesses exponentially by using enslaved people as collateral to get loans.

That’s three layers of wealth building policies for White Americans right there. Subsidized land, subsidized labor, and access to capital. Oh, and for other White men, who maybe worked in finance, you too could get rich, as a middleman, buying up all this slave-backed debt and selling it.

It’s worth mentioning now, because I certainly didn’t learn this in school, that the system was so rigged, so over-subsidized, that when it came to cotton production, the market got flooded with the crop, and the whole thing collapsed. It collapsed under the weight of greed, and at the expense of suffering. And that’s just the beginning.

Perry: Throughout history we’ve always had incredible minds in spite of the atrocities of the work, we’ve always had incredible inventions, and culture, and you know, technology, that were created from people who were supposedly too dumb, not motivated to create. And so for me, I’m always like we need to really understand human potential in a different way. For America, when we understand the potential in Black people, oh, we’re going to see the potential in democracy. You know, it’s the strength that enabled black people to be in this position.

9:56

Gulley: Reframing the narrative to acknowledge what Black people have achieved in spite of White supremacist systems of oppression helps us to center Blackness. Centering Blackness and recognizing the ways in which the Black community has resisted, and persisted, this brings us back to what Dr. Perry said at the very beginning: There’s nothing wrong with Black people that ending racism won’t solve.

Perry: Just, I think if people didn’t rob me of opportunity, where would I be?

And I’m not trying to hear this, “Oh, I came from nothing” crap. No, I came from something, you know, I came from brilliance. My words are my mom’s words, the woman who raised me, and those words came from her mother, you know? So, oh, there’s value.

Gulley: As a White person, I have not had the experience of being devalued based on my race. In fact, quite the opposite. My race has afforded me opportunities — both in ways I understand and ways I may never understand. But yet, I connect personally to some of Dr. Perry’s lived experiences and a lot to his outlook.

Perry was raised in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania by a woman who was every bit his mother, while his birthmother lived just a few miles down the road. And together with other children from all walks of life, his brothers and sisters, they formed a family. Some could look at his experience, judge it and decide that there was so much he didn’t have.

But Perry believes that it was these experiences that gave him strength and belonging and helped him to develop his sense of self. He comes from brilliance. And while the world might devalue his upbringing, he understands just how much it was worth to him.

As I mentioned in our first episode, I was raised with my brother by a single mother who worked so hard to provide for us. But despite all her hard work, we struggled. Often, a lot.

Throughout my childhood and adolescence, there were a number of dinner tables I ate around consistently, a number of different bedrooms I shared or called my own for weeks or months or years, that weren’t under the same roof as my mother.

It would be easy for me to look at my own experiences, my persistence and hard work, the challenges I faced living for so long on what felt like a knife edge, being at times hungry and almost always in debt, and tell you the story of the American Dream. The story of bootstrapping it, pulling myself up, making it. I understand why I would or could tell this story and why so many other White people would do the same.

Those experiences, those hardships, those struggles, those are every bit true and real. And yet in the spirit of holding multiple truths, what is also true is that as a White person in this country, by and large, there are so many more opportunities to get help, support, to rise. Thanks to policies and programs that were designed predominantly by White people for White people in a system meant to benefit White people. For me, those looked like a massive social safety net that afforded me vacations and job opportunities with, I kid you not, the Governor of the State of New York, whose son I went to school with. This wasn’t the kind of safety net that erased the struggles in my day to day, but it was a proximity to power that opened doors and put me on a general trajectory up, towards more and more opportunity. In other words, it was privilege.

13:19

Gulley: Dr. Perry is really driving home this idea for me that policies facilitate wealth. Everyone is working hard. The question is, are policies working hard in your favor?

Perry: We’re in this midst of a pandemic. And it’s clear that wealth protects some people and not others. And when people, after a few weeks of being socially distanced, business owners were demanding relief from the federal government. And, you know, I certainly appreciate that. I said, well, try being socially distanced for generations, what kind of stimulus package do we deserve in that regard?

Gulley I want to learn more about what this social distancing has looked like, and how it has, generation by generation, widened the racial wealth gap.

After enslaved people were freed, they didn’t get that 40 acres and a mule. In fact, that would have been a wealth-building policy. Instead, that was a promise unkept. And after a short period of reconstruction, Black communities faced a backlash and an ushering in of 60 years of legalized segregation under Jim Crow, the legacy of which has left deep imprints today.

Now, we have to take a minute to talk about redlining, an example of devaluation happening at both a policy and a personal level.

14:34

Perry: Redlining was enacted by the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation, the federally backed home owners loan corporation, they drew red lines around predominantly black communities. And they deemed them too risky to lend out loans to people in those areas. Or they did not give them the kind of home assistance, buying assistance as they did other areas.

And we know that that practice robbed Black families during that time of the opportunity buying homes, establishing wealth that they would then pass on to their children and their children, to their children. That practice certainly robbed people of sort of the material goods that drive everything from education to marriage, to a number of things.

But it also set a dangerous precedent of looking at black people as risky.

Gulley: The Home Owner’s Loan Corporation program was created as part of the new deal to provide opportunities for refinancing, prevent foreclosures, and expand home buying to mitigate the impacts of the Great Depression. But, get ready for it, this support was really only available to non-immigrant, White people.

Thanks to the Mapping Inequality Project, organized by the University of Richmond, Virginia Tech and the University of Maryland, I went through some of the maps that the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation made in the 1930s.

The maps give neighborhoods a grade, and a corresponding color from green to yellow to red. An “A” grade stood for the best, “B” grade meant “Still Desirable,” a “C” grade signified “definitely declining” and a D grade represented neighborhoods that were labeled as… hazardous.

The types of things that scored a neighborhood a C grade included, and I’m quoting the actual text of these maps “possible negro infiltration” or “possible encroachments of negroes and Italians.” Can you imagine the rationale that was used to give a community a D grade?

These D grades, with red lines drawn around the communities, were more than just racist maps. They codified, with just one color, that Black neighborhoods, Black assets, Black people were risky investments. And if you were a Black person and you wanted to buy a house, your only options were in these redlined communities. This is because segregation — “White’s only” was often written into the very deeds and covenants of houses in White communities. But thanks to these redlines, you weren’t gonna get a loan. As a result, most often you weren’t gonna buy a house. Dr. Perry explains how the concentration of poverty that resulted from this policy resulted in dangerous narratives about the value of Black people.

Perry: Devaluation has a sort of a policy underpinning but, it’s deeper than that. It’s about how we view black people, how we view others, who don’t share our background. And so, um, but, you know, nothing grows without investment, nothing.

And if you feel that people are too risky to invest, they never grow. I’m always forgetting the name of the Vietnamese philosopher, who once said, when you look at a head of lettuce and it’s not growing, you don’t blame the lettuce. You look to see if the soil has the nutrients, you see if it’s getting sunlight, rainwater. But when we look at black communities, and we see problems, we blame the lettuce.

Gulley: Without the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation or a policy like it, a lot of White communities would have been devalued. A lot of lives and livelihoods would have gone in a different direction, taking longer to recover from the Depression. But the policies heeded that Vietnamese Philosopher – Thich Nhat Hanh’s words when it came to White people, and they were given the nutrients and sunlight they needed to grow – to get back on their feet. The American Dream in action.

Perry We’d all need to unlearn the bullshit around the American Dream. Policy has dictated the fate of many ethnic groups differently, and our dreams have been shaped by those policies that essentially were visions of elite White men, landowners, who wanted to preserve that power for themselves.

We’re going to have to extract these racist policies from markets so that everybody can live the American Dream. And it’s possible, you know, we created these policies. We can create new ones. We absolutely can do this.

19:35

Gulley: Knowing full well that we are skipping over countless other policies, from the GI Bill to Federal Farm Assistance, and beyond, each with their own unique spin on troublingly similar stories, I want to learn more about Dr. Perry’s study of the devaluation of Black neighborhoods in present day.

Perry: After controlling for education, crime, walkability and all those fancy Zillow metrics, homes in black neighborhoods are undervalued by 23%, about $48,000 per home.

Cumulatively, that’s 156 billion in lost equity, essentially. And we know that that’s the money people use to start businesses. It would have funded more than 4 million businesses. Based on the average amount Blacks used to start up the firms. It would have funded more than 8 million. college degrees based on the average amount of a four year degree, it’s a big number.

Gulley: This shouldn’t be surprising, based on the historical devaluation of Black lives, Black assets and Black communities. And yet, I still find it staggering. The racist belief system that Black assets are risky has essentially resulted in a $156 billion dollar tax for owning property while Black. This is the anti-Blackness of our current economy shining through.

Anne Price, President of the Insight Center for Community Economic Development and her colleagues from the economic justice space recently wrote an essay envisioning a world where we center Blackness, as a path towards building economic liberation for all.

Among the many reasons for doing so, they explain that by centering the Black experience, you “steer our bodies, minds, and imaginations in a whole different direction, which can lead us toward true liberation.” Centering Blackness, they argue, allows us to achieve what so many Americans are fighting for: shared abundance, redefined safety, justice and threats, repairing harm, rebuilding trust and relationships, building collective power, and bringing dignity, wholeness and humanity to everyone. When we focus on lifting Black people, we bring the most marginalized groups to the center. In this process, we recognize these marginalized people as valuable.

Dr. Perry shares some of this same sentiment:

Perry: My goal is to show people that “Hey, Black folk, Latinos, Queer folk, whoever’s different, does not make them less valuable.” I mean, actually that makes them more valuable when you think about the diversity needed to uplift a community. That’s talent, that’s innovation that comes along with that diversity. Everything changes when we remove the drags of racism, sexism, and homophobia. And every time we devalue somebody or a community, we hurt ourselves. And so I’m not into cutting my nose to spite my face. And neither should a country, neither should an economy.

22:39

Gulley: I think it’s clear that we aren’t going to close the wealth gap without reckoning with our past. What I don’t get is how we ever thought we would. And yet, instead, we have largely framed the issues of poverty as having to do with individual choices and behaviors.

Anne Price, the person who I mentioned argues for centering Blackness, she explains that this framing has led to proposed solutions like financial coaching or the development of long-term savings plans for children, minimizing efforts to dismantle structural barriers to wealth accumulation

To me, this is akin to the ways that consumers have been tasked with saving the planet through purchasing sustainable products, which cost more and aren’t available to everyone, instead of the government and companies committing to structural changes, through things like policies and regulation.

Framing climate change as a consumer choice problem, and framing the racial wealth gap as caused by bad behaviors. I’d argue this is gaslighting. This is insult to injury. This is shaming: which is a tool that’s been used to oppress people for a long time.

I recently heard authors Saeed Jones and Laurie Halse Anderson work out the difference between endurance and resilience. Endurance is when somebody hands you a bag of shit and you hold it. Yep, I’m enduring. I got this. Still holding the bag, still enduring. Resilience is when you hand that bag of shit right back. And the only way you can do that, is if you shed the shame. If you recognize that this is their shit, not yours.

For too long, our system has handed Black people bags of shit to hold, masquerading as “solutions” to the wrong problems. It’s time to reframe this shaming narrative to a different one: there’s nothing wrong with Black people that ending racism won’t solve. Centering Blackness to create those new policies Dr. Perry was talking about, that gives us a place to start.

24:47

Gulley: Reckoning with our racist past and creating new, anti-racist policies – that’s big stuff. And as we’ve said, it’s work that will take movements of people. Coming from the sustainable business world, a space that is for the most part not informed by anti-racism work, I’ll speak for myself when I say that the solutions I have been generating to address some of the biggest problems with business – driving climate change, exacerbating inequality, destroying ecosystems and communities – have not recognized the layers of oppression on which our current system is built.

Making sure that my field, and others like it are informed by our history and committed to a more equitable future – that’s the direction our compass is pointed.

But as we walk that path, there are other things we can do around the edges. Things we can do today. Right now. We want to understand the very best of what’s happening to drive racial equity within our current system, and for that, we turn back to Randy Strickland, who we heard from once briefly at the beginning of the episode. He was making the point that racial inequality presents systemic risk across our economy as we know it. Randy is the Director of Racial Equity Investing at Cornerstone Capital, an impact investing advisory firm.

Strickland: What racial equity investing is, at least in a US context, is really paying attention to reckoning with our past. And I spend most of my time actually talking to investors who want to do better, but still don’t even understand what the history of the U.S. is. and how we’re still in this situation.

Gulley: Randy goes on to share a very similar history to the one we’ve been discussing this whole episode. He explains:

Strickland: All those contributing factors that occurred, in the past still resonate today. So, we’re trying to address those, and current inequalities in a publicly traded company. A lot of people own stocks. You would look for not only if a company has diversity in its senior ranks, we’re looking at how they treat their lower paid employees, how they treat their average employees.

Walmart for example is employing artificial intelligence, uh, which is a smart thing to do, but who’s affected mostly by that? Those lower tier jobs, cashiers, and stock clerks. Those are people of color and women primarily. So what are they doing to retrain or up train those folks for jobs in the future that require a lot more technical skills. Same with an assembly plant. You know maybe in the fifties and sixties and beyond, to the extent that they would hire people of color, there were jobs that were well paying jobs and one could hopefully have a middle class lifestyle.

Those jobs just don’t exist anymore. They’ve either been shipped overseas or they’ve been replaced by, uh, technological advances. So what are you doing to help those workers in training them? We’re looking at companies that pay attention to that.

Dana G: So in this example, Randy’s firm builds a portfolio of companies to invest in that have the kinds of practices like upskilling and pay parity that help to overcome the inequity that the system as a whole is delivering. He explains that investing for racial equity also means investing to combat climate change, provide access to healthcare, and affordable education.

Randy Strickland: All of these issues are interrelated and investors that will look at those factors will be contributing to reducing inequality in the country and beyond.

There still is some degree of doubt that one can combine their values and their investments and still get market rate return. I don’t fault people for doubting that. But once you’ve seen the data, and all of these studies, it’s certainly not only the right thing to do from a value standpoint, it is just better investing

Gulley: Cornerstone did some back testing with a total portfolio, across asset classes, that invests to drive racial equity. And looking back 10 years, the fund would have outperformed, with a lower level of volatility.

Thanks to firms like Sustainalytics, CDP, and SASB, data has become more robust and accessible than ever. Which is good news, because overwhelmingly this data shows companies with better ESG scores, meaning they are performing when it comes to the environment, social issues, and governance. These companies are outperforming their competitors in terms of financial returns, too.

So, while neoliberal economics told companies – just focus on maximizing your quarterly returns – It turns out the very things that a company externalized in order to do so; pay equity, environmental responsibility and so much more — these things affect the bottom line of a company, afterall.

Hear, hear for the data!

29:50

Strickland: Now we’ve got some of these larger firms like BlackRock and UBS that are, at least they’re saying that they’re demanding this information.

So when you have those big players, as opposed to just this community of small boutique firms like mine, that adds a lot of weight.

So there’s this whole ecosystem here that is helping move things along.

Is the pace of change fast enough? To me, no. But, uh, I’m happy to see some progress over the last 10 years. And I’m hopeful that that will continue, but it’s gotta speed up.

Gulley: So, according to Randy, I can use a lens of racial equity to think about the kinds of companies I’m investing in in order to get, not just my financial returns, but in fact, impact for communities of color. And by investing in companies, or even affordable housing projects, that are investing in these communities, this approach chips away at the massive wealth disparity that we currently have. It helps to appropriately recognize value in the places Dr. Perry has explained, have been so wrongly devalued. While I hear Randy that he is hungry for more change, faster, I want to understand what an individual, say one without a pile of money to invest, can do.

Strickland: CDFIs, acuity development financial institutions, just making deposits or banking through them, actually is the easiest way.

Gulley CDFIs are private institutions that are dedicated to providing responsible and affordable banking services to low-income and low-wealth individuals. Randy explains that access to capital, not to mention basic banking services that many of us take for granted, can be a huge barrier for communities of color. He’s seen firsthand how third-party companies can be predatory, charging folks without bank accounts excessive fees to cash checks or transfer money. This is a problem we see all over the world, not just in the U.S.

Strickland: So some of these community development financial institutions have stepped up and are offering the same services and offering free bank accounts, free checking accounts, and free savings accounts to these communities.

Gulley: Randy explains that CDFIs are making mortgage and small business loans to folks who don’t meet the credit profile that other mainstream lenders without a mission might require. And the more capital they have to work with, the better work they can do in the communities they serve, which is why simply banking with them is a way you can make an impact.

Strickland: There’s really no risk with being with a CDFI versus a larger institution. So that’s, that’s sort of a basic way that people of all incomes can participate.

32:46

Gulley: We’re not going to fix the system through racial equity investing alone. And we can’t lose sight of the need for transformative change. But it seems for more reasons than one, folks who have investments should be channeling those investments into impact portfolios as a place to start. Think of all the money out there that could be channeled to serve a purpose in addition to driving returns. And for any one of us with a bank account, we should be making sure we bank with CDFIs. This is certainly something I commit to doing.

By making these changes, we’re taking a step towards forming that civic family that Dr. Perry envisioned, the one that lives, in his words, under a just, equitable and loving roof. This is the family we’re all looking for.

Thanks to Dr. Perry, I feel like I can see the potential of this mother country, and thanks to Randy, I’m equipped with knowledge of the ways I can make an impact right now.

But there’s work we have to do on ourselves to have the courage to step into the arena.

Perry: Now I’m in a place, I can be me. You know, not, not that we ever become something and that’s what we are. We’re always in a state of evolving, right. But I can evolve at my own pace.I don’t necessarily need someone else’s validation. I don’t need to look at the hot new economist right now and go, “Oh, I need to follow that person.”

No, I can actually follow myself. I’m in this wonderful space now where I’m like, Oh, look at the ideas that come from me, not who I’m supposed to emulate. We all have these great ideas. If we let ourselves nurture them and have trust. Now there’s some ideas that turn out to be bad ideas that I developed, but I can fail and I’m okay. And I can move on.

Gulley: Speaking for myself, and not for Dr. Perry, risking failure and knowing that you are safe – that takes courage. And in all honesty, for some of us, it takes therapy, to help understand the body’s trauma response to real or perceived failure. This has been my work over the past year, and it’s opened up so much in my life.

In a recent podcast with Brené Brown, Sonya Renee Taylor, Founder of “The Body is Not An Apology,” talks about natural intelligence. How we have what we need inside of us, and our work individually is to remove the barriers that are in our way, keeping us from becoming what we can become. It’s so important to remember, there is individual work and autonomy in all of this. And if each of us is doing what we can to remove the barriers within ourselves, we can come together to do the work of the collective – in this case, transforming policies and uniting towards a new vision for our society and the economy that enables it.

This kind of vulnerability – to face ourselves and one another – also takes courage.

But let’s remember, courage is contagious, and when we practice it, we help to make the world a little braver.

Thanks to the help of our guests, I have had the courage to open my eyes wide, to see just how broken the system is. From this place, I’m finding that I can see civic siblings all around me, with their eyes and minds and hearts wide open, working for real change. Not the glossed-over version. Not the feel good instant gratification version that can be so tempting.

But the true liberty and justice for all version.

Our work is to continue to bring these voices together, learn from them, and with your help, build momentum.

Are you with us?

Gulley: Credits

As always, we have a team of people to thank for their help creating this episode of Decade of Courage.

First and foremost, our heartfelt thank you goes out to our guests: Dr. Andre Perry from the Brookings Institution and Randy Strickland from Cornerstone Capital, who entrusted their stories and work with us. We hope we did it justice.

Thank you always to Diane Abruzzini, our Community & Design Lead from Mind Frame Digital who gives us so much and our Community Development Manager, Siena Spitzer.

We are so grateful to our Editorial Committee – Julie Keck and Amy Hall — for all the time and energy they give to this project.

There were countless folks who have gone above and beyond offering their support and feedback to help us always work towards improving — you know who you are. Thank you.

Our music just keeps getting better and better thanks to Brian Crimmins AKA MMINS, who composed, edited and mixed it all for Decade of Courage, and a crew of talented musicians. Phil Collier on Keyboard and Percussion, Miles Tucker on Saxophone, Wayne Tucker on Trumpet, RJ Williams on Drums and Percussion, Eric AKA “Slim” Miller on Electric Guitar and MMINS on Bass, Guitar and Percussion. Justin Murrell was our Associate Music Producer and Danielle Walker AKA INEZ was the Assistant Engineer.

Sound editing and mixing by the ever-patient Neato Sound.

Brought to you by Third Peak Solutions, a consulting firm working to transform the way we do business.

This episode is dedicated to my mom, Nanci Ingram, for her super-human strength and courage and to my late father figure, Peter von Bergen, and the many other members of my found family.

And it was written and produced by me, Dana Gulley.

Additional Resources: